Why French Taboulé Isn’t Really Tabbouleh

Food is never static. As dishes travel, they adapt—shaped by ingredient availability, palate preferences, and cultural norms. Few dishes illustrate this better than tabbouleh in France. Ask someone in Lebanon or Syria about tabbouleh, and they’ll describe a green, herb-heavy salad where parsley dominates. In France, where I currently live, many will associate it with a chilled couscous salad barely flecked with herbs. The name is the same—but the essence has drifted.

As a child of immigrant parents—an Egyptian father and a Syrian mother—tabbouleh has always been part of my diet. Summers spent in Syria throughout my childhood and early adulthood etched into me what the dish truly is: a parsley-forward salad, bright with lemon and mint, where burghul is just an accent. Later, after living in France on and off for nearly twenty years, I was struck by the French version: a couscous-based salad with only a whisper of herbs. It intrigued me. How could a dish I knew so well look and taste so different in France? For years, I’ve tried to wrap my head around this culinary drift, yet I’ve never seen any real documentation on how tabbouleh was transformed, or “lost in translation,” on French soil.

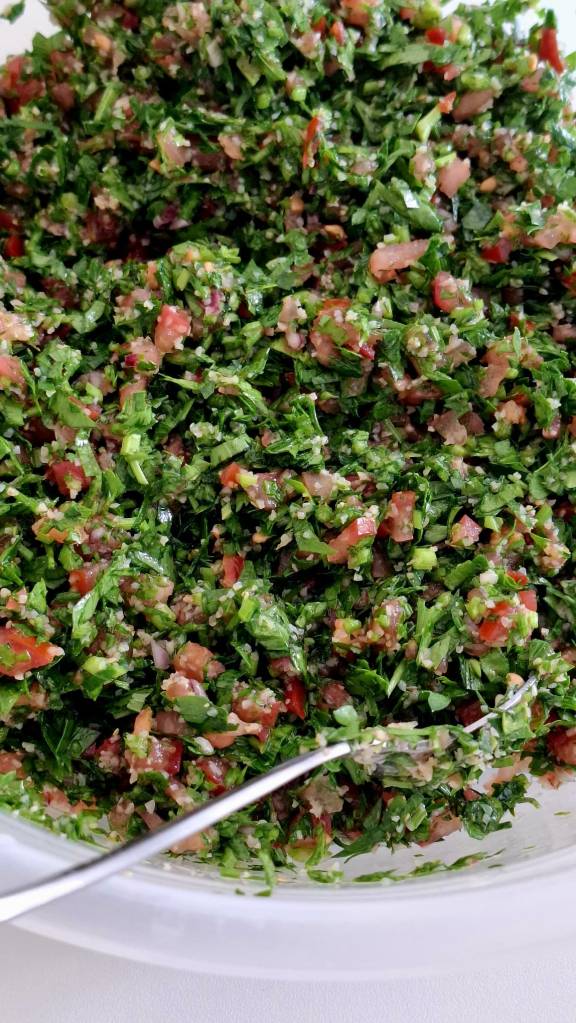

The Original: Parsley First

In its Levantine roots (Lebanon, Syria, Palestine), with origins traced back specifically to the mountainous region of Lebanon and Syria, tabbouleh is fundamentally a parsley salad—not a grain dish. With finely chopped parsley as the star, it pairs with tomato, mint, onion, lemon, olive oil, and just enough fine burghul for texture. Typical home-cooked ratios lean heavily green: roughly six parts parsley to one part burghul, sometimes even less grain. The hallmark is brightness—herbaceous, acidic, and light. The grain is a whisper, not a foundation.

Of course, every region and family may add their little twist. For example, I know Lebanese cooks who add cinnamon or seven-spice, something I absolutely did not see growing up in my Syrian side of the family. But the base must include the seven ingredients I mentioned: parsley, mint, tomato, onion, lemon, olive oil, and burghul—with parsley always as the predominant ingredient.

In Lebanon and Syria, tabbouleh is woven into daily life and celebration. Personally, I never saw a wedding, a large family dinner, or even a restaurant menu in Syria without tabbouleh among the many dishes crowding the table. At the market, heaps of parsley were impossible to miss, and there were even women who specialized in chopping it, selling it pre-chopped—an early form of convenience. We always had conversations about which aunt of mine made the best tabbouleh.

As for my Lebanese friends, they take tremendous pride in tabbouleh as a cornerstone of their culinary landscape, much like bread or rice might be elsewhere. For us people of the Levant, it was never just a side dish but a marker of identity and abundance. We all grew up with parsley stuck between our teeth, and that, too, was part of its charm.

A History: How Tabbouleh Arrived in France

Tabbouleh likely made its first real entry into French food culture via Lebanese migration in the mid-20th century. Starting in the 1940s and 50s, political conflict and economic opportunity drew Lebanese families and entrepreneurs to Paris and other urban centers. They brought their traditions—including cuisine. Lebanese bakeries, cake shops, and small cafés opened, introducing French diners to mezzes, kibbeh, and, eventually, tabbouleh.

In the Paris region, where I am based, there are now countless Lebanese restaurants. I would even argue that Paris is the capital of Lebanese restaurants in Europe! And at these restaurants, you will find the original, very green tabbouleh.

Yet despite the sizeable Lebanese diaspora, this famed salad still got lost in translation.

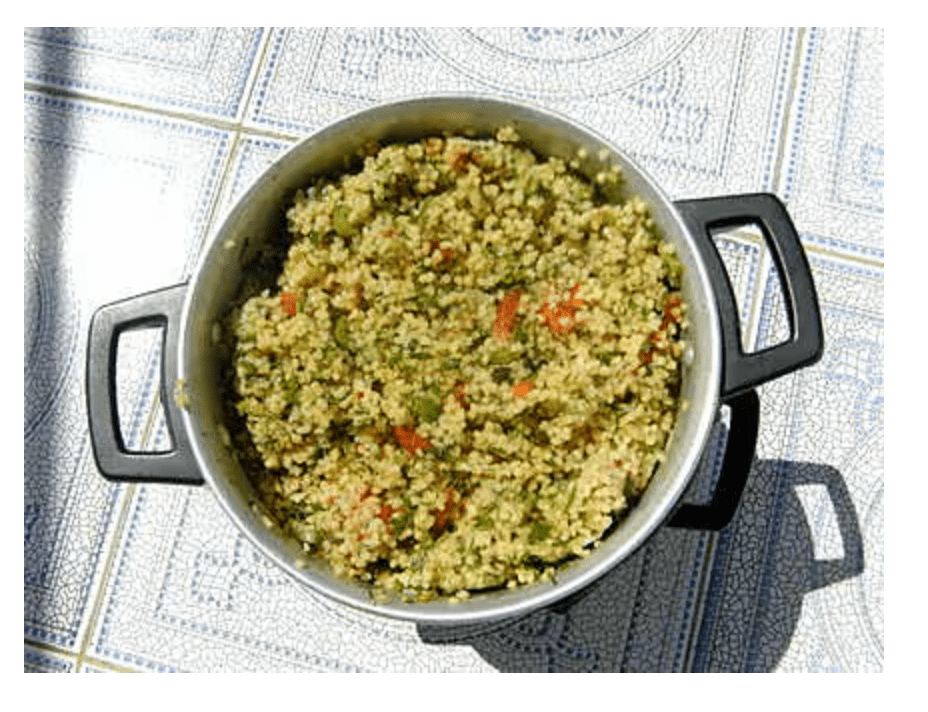

Why the Dish Shifted: Couscous Replaces Burghul

When French cooks and supermarkets first attempted to replicate tabbouleh, they ran into a snag: burghul wasn’t widely stocked in French stores. In contrast, couscous—thanks to North African immigration and colonial ties—was everywhere. Cheap, quick, and well-known, it became the default swap. But the shift went deeper than ingredients.

France already had a robust culture of composed, chillable salads—pasta, lentils, rice—that could be scooped into tubs at cafés or supermarkets. Some popular brands of these convenience, starchy salads are Bonduelle, Pierre Martinet and Garbit- to name a few.

Tabbouleh was recast to fit this mold: the grain became central, and herbs moved into the garnish slot. By the 1970s and 80s, industrial production codified the change. Commercial taboulé lost most of its parsley, used oil instead of lemon-forward zing, and sometimes folded in sweet additions like raisins or corn. I have even seen mass-produced French taboulé with “curry spice” in the mix. Meanwhile, couscous kept its texture under retail lighting, whereas chopped herbs would discolor.

Colonial Ties and Couscous in France

France’s colonial ties with the Maghreb—Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia—also played a decisive role in shaping the French version of tabbouleh. Couscous, already central to North African cuisines, became deeply embedded in French kitchens throughout the 20th century, thanks both to migration and to the symbolic place couscous held as a “colonial ingredient.”

Within the Maghreb itself, there exists a dish called safsouf/seffa/mesfouf, a couscous preparation that can be sweet (with dates, almonds, or raisins) or savory (with steamed vegetables). The savory style in particular, a lighter and more vegetable-forward couscous recipe, may in fact have been a conceptual bridge toward what French supermarkets now sell as taboulé. And I’ve even seen a mysterious “sefsoufé” at a traiteur one day, with the dish looking quasi identical to French tabboulé. Seen through this lens, French taboulé is less a mistranslation of Levantine tabbouleh than it is a hybrid—where the Levantine parsley salad met North African couscous culture and adapted itself to the French market.

Above photos L to R: Fava bean Mesfouf/Safsouf from @oh_pays_gourmand on cookpad.com; another Tunisian variation featuring fennel fronds, photo by Dominique on LesFoodies.com

Above: Sefsoufé spotted at a traiteur in the Paris region. The ressemblance to French taboulé is cunningly similar.

The French Palate and Minimalism

Beyond ingredient history, cultural aesthetics also explain why French taboulé looks the way it does. French gastronomy, since the 18th century, has prized a certain restraint. Thinkers and chefs of the Enlightenment era argued that over-spicing or over-herbing food was vulgar; true refinement lay in showcasing a few noble ingredients with elegance.

That philosophy still lingers, making French diners less receptive to a salad dominated by heaps of parsley and mint. Herbs, in this context, are seasoning, not substance. Add to that a social practicality—nobody wants to be caught with green flecks of parsley between their teeth at a Parisian picnic—and the French preference for a grain-heavy, minimally herbed taboulé makes cultural sense. What Levantine cooks view as essential abundance, French taste reframes as excess.

I’ve also heard anecdotes from friends with years of catering experience in the Paris area who told me their customers simply didn’t want a parsley-studded smile.

When Language Solidified the Identity

The French spelling taboulé—close enough in sound to tabbouleh—made it seem authentic. Few questioned whether “taboulé” in a supermarket cooler was the same thing. Over time, public perception followed the product, especially when that product had become the default “tabbouleh” for many French palates.

What This Story Tells Us

This isn’t just a culinary quirk—it’s a tale of how dishes adapt. In France, taboulé emerged from available grains, shopper expectations, and the supermarket portable-salad culture. It’s an example of how immigration and retail shape our food identity: a Levantine grandmother and a Parisian shopper can say “tabbouleh” but picture very different plates.

A Way to Reconnect

These days, thanks to the internet and social media, many Lebanese and Syrian chefs and food enthusiasts have been very vocal about tabbouleh vs. taboulé. One I’ve followed for quite some time is Kareem, known on Instagram as @thevoicenotechef. Kareem shares his mother’s tabbouleh recipe with his audience and single-handedly started a #SaveTabbouleh campaign.

While I will include my personal recipe at the end of this article, here are some tips if you want to

reclaim the Levantine version:

-Use fine burghul instead of couscous. Fine burghul is very easy to work with—don’t let it intimidate you.

-Chop all your ingredients first, and leave parsley and mint until the end so they don’t turn dark.

-Place your chopped tomatoes in a sieve over a bowl, and use the collected juices to soak the burghul.

-Be generous with lemon juice. A hallmark of Levantine cuisine is citrusy brightness.

-For the onions: adjust to taste. My grandmother (RIP) used to use less onion in her tabbouleh.

-You don’t need to peel or de-seed the tomatoes. Chop them whole.

-Use the best quality extra-virgin olive oil you can find.

-Let the salad rest briefly to marry the flavors; the result should be green, tangy, and light.

-And most of all, make it with love. Love is always the secret ingredient to all great tasting food.

Tabbouleh

Ingredients

2–4 tbsp fine burghul (bulgur)

3 medium firm, ripe tomatoes

1–2 spring onions (scallions)

3 large bunches flat-leaf parsley, tough stalks removed

Small handful fresh mint leaves

Freshly ground black pepper

Salt, to taste

Pinch of ground cinnamon (optional)

Juice of 1 large lemon

¾ cup extra-virgin olive oil

Directions

Wash the parsley and mint, then dry thoroughly and set aside.

Dice the tomatoes into very small cubes. Place them in a strainer set over a bowl or deep dish, allowing the juices to collect.

In a small bowl, soak the burghul in the reserved tomato juices until softened.

Finely slice the spring onions and place them in a large mixing bowl. Season with a little salt, black pepper, and a pinch of cinnamon (if using). Let rest briefly to mellow the flavor.

Finely chop the parsley and mint leaves.

Add the chopped herbs, tomatoes, and soaked burghul to the mixing bowl.

Dress with lemon juice, olive oil, and additional salt to taste. Toss gently to combine.

Taste and adjust seasoning as needed.

Serving suggestion: Enjoy spooned into crisp romaine lettuce cups, or cheekily with a side of fries.

Leave a comment